Despite this, before this module I had very little experience and no confidence in recording audio. The lack of confidence was probably a consequence of the lack of experience in this field. As a beginner, being aware of the various issues sound recordists face - unwanted noise/noisy environments, the art of microphone placement, mic/pre-amp noise, etc. - can give the impression that sound recording is a very scientific and precise, and ultimately difficult thing to do.

Over this module, my impressions on sound recording have changed as I’ve learned more and gained more experience. I have learned that a certain joy can be had from experimenting with different recording techniques and equipment, and that often the best results are the most unexpected ones and tend to occur the more creative you get in your recording, and the more you have while doing it.

I learned this during a workshop earlier-on in the module, in which we were given a selection of microphones and told to choose two different types and spent a set amount of time collecting sounds with our choices. I chose the Rode NT4 and a pair of Aquarian Audio hydrophone mics. I decided to place the two hydrophones onto the sides of an escalator using the rubber contact-mic converters. This produced an interesting low-frequency rhythmic and pulsating sound. This made me realise that these contact-mics were, in a way, able to capture sounds in ways that that our ears would never pick up, because they pick up sound in a different way to human ears - however, I was brought back to the real world when I was told by a member of staff in the place I was recording that I had to stop because, understandably, the microphone cable trailing across the top of an escalator was a health-and-safety concern.

I came to appreciate real-world recording with the Rode NT4 shortly after, when collecting atmos recordings for my documentary module, which required me to find somewhat remote locations and record, which I did at night-time to minimise the number of disruptions. I have found that atmos-track recording can be quite relaxing as it forces you to pay attention to self-made sounds, and sounds around you - which is something that people often forget due to the distracting nature of many modern technologies, such as MP3-players.

I chose the Coen Brothers’ ‘No Country For Old Men’ for the sound-to picture Exercise 1, because it appeared to be the most straight-forward and the least “daunting” choice for my first attempt at a sound-to-picture exercise. I feel that this was both a good choice and a bad one. I gained experience and confidence from recording atmoses and foley sounds for the piece, and gave consideration when preparing the atmos recordings - to create the sound of an American hotel room, I recorded the sound of an American sitcom playing in a different room to the microphone, using the technique of worldising, which is the process of ‘playing back existing recordings through a speaker or speakers in real-world acoustic situations, and recording that playback with microphones so that the new recording so that the new recording takes on the acoustic characteristics of the place it was “re-recorded”’ (FilmSound.org). However, due to the minimalistic nature of the film in relation to its sound requirements, I feel I didn’t push myself very much to develop wider sound design skills such as creating and making use of designed sound or music/musical elements.

Nevertheless, I feel I learned from the experience gained from this exercise and from the feedback given both from other students and from my lecturers. I had mixed most of the sound in the Protools studio on fairly loud speakers. This led to the levels of the sounds in my mix peaking well below -20dB, which meant the playback was very quiet when I presented the work (although this at least shows that I was mixing with my ears according to what the speakers were feeding me, rather than mixing with my eyes being fixed to Soundtrack Pro’s VU meters). From the feedback given, I have learned that the correct levels to mix sound for film at are: between -20dB and -12dB for dialogue, and below -20dB for atmoses and ambient sounds.

I also learned from the feedback I was given that most of my sounds underwent very little processing to enhance the tone of the sound design. This is largely because of the minimalistic approach I took, and while this was deliberate, it probably didn’t enhance my skills as much as it would have had I been more creative in my approach. After completing Exercise 1, I watched the scene from ‘No Country For Old Men’ online and was able to reflect on the storytelling-related details in the original sound - such as the sound of someone offscreen unscrewing a lightbulb, which in the film is a significant, but subtle, touch. However, being unfamiliar with the film, I wasn’t able or required to have this level of input in telling the story of the scene. Overall, this exercise helped me improve my skills and develop a better and deeper understanding of the processes that go into film sound.

After lots of consideration, taking into account what I had learned from Exercise 1, I chose the clip from Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro’s ‘Delicatessen’ for my Major Project. As well as what I’d learned from Exercise 1, I was inspired to make this choice from a workshop during the module in which we collectively went over each of the choices, comparing the sound requirements of each, and also by the strong and moody visual style of the clip. I felt that this clip would give me an opportunity to combine the foley techniques I developed earlier in the module with new approaches to sound, as the opening sequence clearly required a strong designed soundtrack to match the picture.

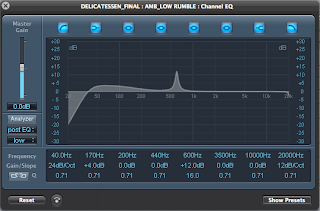

To match the postapocalypse-esque wasteland seen in the opening sequence and the very strongly orange-coloured visuals, I used a sound I had originally recorded but ended up not using for a poetic documentary I made for another module. The sound came about from recordings I made while holding a pair of tie-clip microphones down roadside grates on a windy night. The sound of the wind resonated and reverberated within the drains, and the recordings alone produced a powerful low-frequency “rumble”, which I later processed in sound editing software, the process of which I outlined on my blog for this module. Taking feedback from Exercise 1 into account, I processed this “rumble” to sound something like wind, which I achieved by boosting a particular frequency using Soundtrack Pro’s channel EQ and using automation to boost the gain of this frequency over time, and also to change the frequency to give the feeling of movement within the sound (evidenced in the following screenshot).

In order to quickly set the tone of the clip immediately, I combined this wind sound with a series of chords played on a synthesised organ in the music software Reason. Only having basic understanding of chord structure, I chose to progress from a minor-sounding chord to a major chord and then to a dissonant-sounding chord, in part to create a sense of drama, as major chords tend to sound “happy”, which is then contrasted by the “scary-sounding” dissonant chord, shortly followed by the sound of a knife being sharpened. The “cheesiness” of this music was also intended to add a slightly humorous element to the overall mood to match the dark humour seen in the clip.

The sound of the knife being sharpened preceeds the introduction of the Chef or even the kitchen setting in order to add a sense of unease, as hearing before seeing typically invokes a sense of curiosity in the audience, which in this case is intended to encourage the audience to question why a knife is being sharpened in that desolate landscape. Again, learning from feedback from Exercise 1, the knife sound is “drenched” in reverb, largely to add the sense of horror that comes from exaggerated and somewhat unrealistic sounds.

In contrast with Exercise 1, for which I chose to explore the sound from the main character’s point-of-view, I decided to follow the camera’s point-of-view for this task, and so added details such as being able to hear the Chef breathing heavily as the camera passes over his shoulder.

Because the knife sound has to be heard when we enter the (for lack knowing the character’s real name) Victim’s bedroom, the reverb presented a potential problem as the camera moves through pipes, as this would typically be where reverb naturally begins to overwhelm the original sound. To compensate, I added a stereo delay effect and automated the mix balance

I also experimented when creating the sound of the bin lorry. This was composed of three different recordings, which were each EQed to fit together without “clashing” due to overlapping in sensitive frequency ranges. The first sound introduced is taken from a recording made using two contact mics on the sides of an escalator, which was intended to act as the low-frequency engine sound of the lorry - however, because of the rhythm the escalator gave to the recording, this also worked well as a musical element to help the sequence beginning in the bedroom and ending when the Victim is shown to be hiding in the bin flow and add a sense of suspense to the soundtrack.

I then added recordings of boiler rooms which I collected when I was allowed access to plant rooms inside Sheffield Children’s Hospital to both serve as a piercing high-frequency sound, and as a mid-range-frequency used to show the movement of the lorry, which cuts out when the driver brakes. The high-frequency sound is introduced before the scene moves outside, and this is largely because, when mixing I realised I hadn’t recorded any sound to use when the Chef runs his fingers along the knife. However, I feel this worked in my favour, as I was able to use this sound to represent this as well as to introduce the bin lorry before it appears on screen. Again, my approach to creating the sound of the bin lorry was centred on creating something that sounded unreal and, hopefully, scary, rather than using the sound of a real engine, as this I felt would be too mundane and wouldn’t keep consistency with the soundtrack.

The last new sound effect (“new” meaning a sound that hasn’t already been introduced in the project) used for my Major Project was the “thud” sound as the Chef swings the knife towards the Victim, just as the title appears on-screen. This was created using a pitched-down recording of a bag of compost being dropped onto the floor of a shed. The sound alone, even when pitched-down and EQed, didn’t have enough impact. To solve this, I applied a compressor to add “punch” to the sound. I began the compression by setting the threshold low and using the attack and release controls to time the compression appropriately. I followed a guide written to explain how to set-up a compressor for a snare drum and shortened the attack setting until the sound began to dull (Owsinski 2006, p.62) and then ease the threshold back until the thud had the right level of impact.

Overall, I feel I have progressed a lot throughout this module and have used the skills taught to good effect on my Major Project.

References

- FilmSound.org. Worldizing: A Sound Design Concept Created By Walter Murch. [online] Available at: http://filmsound.org/terminology/worldizing.htm [Accessed 20 December 2012].

- Owsinski, B., 2006. The Mixing Engineer’s Handbook. 2nd ed. Boston: Thomson Course Technology